I carred (just coined) from Dehradun to Delhi to attend the ANZAC Day Dawn Service at the Delhi War Cemetry on 25 April 2022.

One way or the other, I have been involved with ANZAC Day dawn services since the 70s. In Lebanon, Syria, Libya, Solomon Islands and finally in India, Since my posting ended in New Delhi, and if I am in India, I have maintained the personal tradition of attending the Dawn Service at the War Cemetry. It is always a touching experience, whatever the location.

This personal connection with Gallipoli dates back to Doug McLennan, my first boss at David Fell & Co., Chartered Accountants, where I was an apprentice in my mid-teens. His family had had multiple casualties in the First World War, including in Gallipoli; most Australians in the 1960s did. He took me to my first Service at the Canberra War Memorial. That was more or less my first introduction to the sense of Australia and its culture (after the 1Sh8p fish and chips at the Griffith shops).

Inevitably, yesterday, I reflected on the ANZAC gatherings I had witnessed over the last 50 years. As late as 1994, at my first Service in New Delhi, I recall being viewed as an oddity with my brown visage among the (little) pond of Oz, NZ and Brit Whites. Even the 2 or 3 Indian Armed Services representatives authorised by the External Affairs’ babudom to attend looked askance at me, ever vigilant of 5Eyes’ activities. Over the next six years, the crowd grew from 30-odd to around-70 odd (as more Australians came to India).

But the most notable difference between then and now is that at the time, we never acknowledged the role of around 1mn Indian servicemen in WW1 – from Flanders to Somme to Gallipoli. Some 75000 perished. 2mns served in WWII; some 86000 perished. (Incidentally, Gandhi had been an ambulance orderly during the Boer Wars.)

A 1997 visit to Brighton in the UK, specifically to the stately home, the Brighton Pavillion, which had been converted to a hospital for (the segregated) Indian war wounded, prompted subsequent research at the AHC. For the first time in 1998, the then Australian High Commissioner, Rob Laurie, included a brief tribute – we had not cleared the matter with Canberra – to the Indian role in Gallipoli. I can confidently attest that it came as a surprise to many at the Service, including the Indian representatives. I recall mentioning this during a call on General Sundarji, Chief of Indian Army Staff, lying ill at the Military Hospital. He was fully aware of the Indian contributions and expressed his irritation at the ignorance. But he had never attended an ANZAC Day service. He said he would check with the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun.

Yesterday, the wartime camaraderie and cooperative contributions between ANZAC and Indian troops were fulsomely acknowledged by the speakers and well received by the representatives of the Indian armed services. Notably, Indian – Australians, barely evident 28 years ago but prominently present at the Ceremony, were very appreciative of the Australian High Commissioner’s remarks.

Two digressions. One, after the Indian nuclear tests on 11 -12 May 1998, it was informally suggested that such initiatives were best left alone. Two, there is no doubt that though we and NZ knew very little, the Brits were obviously well aware of the role played by Indians in Gallipoli in the service, ironically enough, of their Imperial masters. But I do not recall the British High Commission at any time mentioning or acknowledging this aspect in our preparations for the ANZAC Day Ceremony. Perhaps that was one measure of the subliminal love-hate relationship that existed then between post-Independence India and Britain (in contrast to their – and Australian/US relations – with Pakistan at the time).

One of the more sombre but pleasant tasks I undertook was the inspection of cemeteries preserved by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. It was a requirement to inspect and approve the standard (and the price) of maintenance of the cemetery by local caretakers, inevitably descendants of war-killed fathers. I visited Imphal, Pune, and Calcutta. Their memories were still fresh and revealing. and they were maintaining the cemeteries immaculately.

I last visited Gallipoli in 2018. Much had changed over the years. The calm and reflective environs had given way to flocking crowds, dusty paths replete with many young Australian boors, often thonged and bare-chested, intent on recharging their beer tinnies. Overheard conversations had nothing whatever to do with Australian memories or spiritual connections that Gallipoli represents.

My one and only discordant note on ANZAC Day occurred in 2002. In my (unsuccessful) entry to the Horne Essay Prize in 2016, I wrote: “In 2002, at ANZAC Day dawn services in Canberra, anxious glances blitzed me. An AFP uniform sidled up. Clearly, I was a ‘person of interest’. It was prudent to retire hurt. Ironic. Having coordinated the upkeep of diggers’ laden cemeteries at various postings overseas, participation in ANZAC Day services has become an annual emotional pilgrimage.” Please note that this encounter was in the aftermath of 9/11. I understood, but it rankled then. My Essay “My Travels with Australia Fair; a Fading Affair” is accessible on this site under the IMeMyself/Reflections Category.

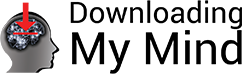

One of the most touching moments in the ANZAC Day ceremony is when the Turkish Ambassador is invited to say a few words. It is a generous invitation by the ANZAC allies and equally an ungrudging Turkish acceptance to participate. This aspect of sharing a tragic occasion is encapsulated by the bust above of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk from the memorial at Gallipoli, honouring ANZACS and the Turks who died in those unforgiving fields. The inscription, attributed to Atatürk, pays tribute to his former foes and reflects his understanding of the cost of war:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore, rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours… You the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.”